Beginner’s Mind: At Work in the Writing Center

by Cheryl Chaffin, Outgoing Writing Center Director

by Cheryl Chaffin, Outgoing Writing Center Director

Working in Cabrillo’s Writing Center from 2011 to 2015 has brought me back to beginner’s mind. That mind belongs to the new student as she begins to write and think academically. It emerges as she reviews and responds to her instructor’s assignments. In this tangled engagement, she might discover her unique mind and its idiosyncratic writing voice. I had forgotten what it was like in the very early months and years of starting an endeavor for the first time. One has still to learn the rules and, later, bend them to her purposes. At the same time, the rules of writing—as they apply to any given discipline—should, and do, shape the student.

The beauty of my work in the Writing Center, from the dual perspective of English instructor and a director-sometimes-writing-tutor, has been the precious opportunity to sit next to and with students in immediacy of the writing process. It is then that I’m witness to something seemingly secret, hidden from view, in the classroom. The personal relationship between student and assignment begins to manifest. The student sits in the midst of the swirling, confusing, and sometimes liberating process of creation. What does she want to say? What is the sound of her mind? Does she have a voice? These questions are often terrifying, formidable, or intimidating to the student. They swirl in the air about our sessions. I had forgotten that most of the time we have no idea what we want to say, how to say it, or that we are able to say it. The entry into an assignment is a portal into a deep world of emerging thought coupled with the deliberate and academic nature of planning. We often pause, student and tutor, on the threshold of this portal before diving into the long, arduous journey of composing.

As an instructor, I had not often witnessed close up students’ private, personal struggles with the writing assignments we give them. An African American student who did not want to write about race wrote around it that first essay. By the time he had reached the second essay, he began to look at issues of race, writing of neighborhood basketball games on his home court of Oakland. His language and voice begin to emerge. He had hit a stride that carried him (dare I say, elevated him?) into a third essay where he wrote directly of race and how it affected his path in life, specifically his relations with his parents. Natalie Golberg, Zen writing teacher of Writing Down the Bones and Wild Mind: Living the Writer’s Life, recommended writing about what you do not remember. In the same way, this student had to write about everything but race in order to get to the ways that race and all its contingencies have shaped his life experience. What did I learn? Sometimes a student resists, for good reason, our teachings, writing himself toward a topic and its themes circuitously and with appropriate caution. Resistance is a necessary good and can be a delicious, even if painful, energy for writing.

As an instructor, I had not often witnessed close up students’ private, personal struggles with the writing assignments we give them. An African American student who did not want to write about race wrote around it that first essay. By the time he had reached the second essay, he began to look at issues of race, writing of neighborhood basketball games on his home court of Oakland. His language and voice begin to emerge. He had hit a stride that carried him (dare I say, elevated him?) into a third essay where he wrote directly of race and how it affected his path in life, specifically his relations with his parents. Natalie Golberg, Zen writing teacher of Writing Down the Bones and Wild Mind: Living the Writer’s Life, recommended writing about what you do not remember. In the same way, this student had to write about everything but race in order to get to the ways that race and all its contingencies have shaped his life experience. What did I learn? Sometimes a student resists, for good reason, our teachings, writing himself toward a topic and its themes circuitously and with appropriate caution. Resistance is a necessary good and can be a delicious, even if painful, energy for writing.

What is the secret work of a Writing Center? The intellectual and creative intimacy of student-tutor work is precious and rarely articulated. It happens sometimes, as if by magic, but it is not magical. It is serendipitous, occasional, incrementally transformative and potentially far-reaching. As a tutor, I’m a student’s reader, audience, listener, and interlocutor. I’m the grease in the student’s mind that cranks gears and churns thoughts buried within. My questions the student answers. She hears herself in the echo that I become of and for her. Tell me why, I say. And, returning to me, a river of unearthed thoughts, I hear narrative, critique, or response as it enters the sensate world. Write that, I say. We sit (oh, this rare sitting, to be fully present with another), me waiting and contemplating this momentary space, she writing the words that are hers.

Beginner’s mind has reminded me of writing’s work—how writing whittles us to our essences. To write is to have a world, to have a language, to try various new languages and fit them to your life. To write is to learn, to experiment, to sometimes fail, and to create with abandon. To write is to discipline the mind to higher purposes than those dictated by habit and desire. It is to think of and towards others, to invite them into your world. To write is to take on the risk and vulnerability of others’ responses to your thoughts—all those counterarguments and refutations we want students to imagine and inhabit. To write is to expose oneself. To write is to have a voice, and by extension a self, that dwells in the ideas that appear on the page. To write is to trace the contours of one’s mind in response, carved by and in relation to the world. It is risk, a strange kind of love entangled with struggle, attuned sensibility, and outrageous courage.

Writing has a tendency to make itself one-dimensional, flat on the page. We writers not infrequently lose the joy and vibration of good language and inspired storytelling. I want to make this good, says one student, writing of her father in his machine shop, how those childhood experiences made her want to become an engineer. She’s from Colombia, her first language Spanish. She’s bored with her writing and doesn’t know what to say. Stuck: the wall that all writers confront and through which we must hack if we are to continue. Tell me the story, I ask. She does, but not enough. We are never writing for one, always for an audience, I remind her, so you have constantly to write more than you think you should. Tell me what you see. A few more details: the wooden wings of airplanes, the grind of metal. Where are you? From what vantage point are you saying this? Make me you, I push. She continues to talk and the story grows and deepens, becoming increasingly rich with sensate and mnemonic detail. I take my leave as her story, the answer to each question in the assignment, continues to grow. She has found her way through a forest of memory and word.

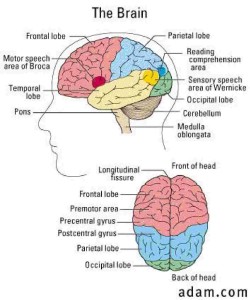

For many students, revision is crucial. If a student avails himself of any opportunity to revise, he may improve his writing skills and acquire a more thorough knowledge of the forms of academic writing than he would without the benefit of revision. He has so much to learn and each time he reenters the act of writing he has space to organically integrate the answers to questions like: what does it mean to respond to a piece of reading; what does it mean to have an opinion; what’s the transformation from opinion to informed position; how does one have a dialogue with the world, with other thinkers and writers, with ideas and events; what does it mean to strengthen the thinking organ of the mind; how might that strengthening and the material that nourishes intellectual maturation change me over the course of my lifetime? Revision is a kind of redemption. It reminds us that writing is never done and that it does not require perfection, though it does demand mastery and the patient diligence of repetitious work.

In the Writing Center, a desire for verticality—going deep—can lodge itself in the student’s mind as she works and interacts with her tutor and engages the assignments of a course. It is these exchanges that have shaped my tutorial space and time. Ultimately, it is with the quiet insights of tutoring that I return to the classroom for further encounters with students in the writing process.